All About Arabic Music

Arab Music - Part

One

by

Ali Jihad Racy, Ph.D. and

Jack Logan, Ph.D.

"I believe the soul is immortal"

--Abu al-Walid Muhammad bin

Rushd (1126-1198)

Arab music

Contact with

Assimilated Cultures

The first process took place during the early centuries of Islam,

with the growth of cosmopolitan cultural centers in

Court affluence and acquaintance with the worldly splendor of

conquered empires stimulated humanistic interests and artistic and

intellectual tolerance on the part of the Arab rulers. In a short

time court patronage of poets and musicians became common practice,

in contrast to the antipathy of some early Muslims towards music and

musicians. The Abbasid caliphs al­Mahdi

(reigned 775-85) and al-Amin (reigned

809-13) are particularly known for their fondness for music. In

contrast to the quynat, or female slave

singers, who were prevalent during the early decades, the emerging

court artists were often well-educated and from distinguished

backgrounds. Among such artists were the singers and scholars Prince

Ibrahim al-Mahdi (779-839) and

Ishaq al-Mawsili

(767-850), and the 'ud (lute) virtuoso, Zalzal

(died 791), who was Ishaq's uncle.

Contact with the

Classical Past

The second process was marked by the introduction of scholars of the

Islamic world to ancient Greek treatises, many of which had probably

been influenced previously by the legacies of ancient

The outcome of this exposure to the classical past was profound and

enduring. The Arabic language was enriched and expanded by a wealth

of treatises and commentaries on music written by prominent

philosophers, scientists, and physicians. Music, or

al­musiqa, a term that came

from the Greek, emerged as a speculative discipline and as one of

al­ulum

al­riyadiyyah, or "the mathematical sciences,"

which paralleled the Quatrivium

(arithmetic, music, geometry, and astronomy) in the Latin West. In

addition, Greek treatises provided an extensive musical

nomenclature, most of which was translated into Arabic and retained

in theoretical usages until the present day.

Theoretical treatises written in Arabic between the ninth and the

thirteenth centuries established an enduring trend in Near Eastern

musical scholarship and inspired subsequent generations of scholars.

An early contributor was Ibn al Munajjim

(died 912) who left us a description of an established system of

eight melodic modes. Each mode had its own diatonic scale, namely an

octave span of Pythagorean half and whole steps. Used during the

eighth and ninth centuries, these modes were frequently alluded to

in conjunction with the song texts included in the monumental

Kitab al - Aghani, or Book of Songs, by Abu

al­Faraj

al­Isfahani (died 967). In this system, each mode was

indicated by the names of the fingers and the frets employed when

playing the 'ud.

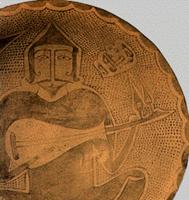

Lute (from the Arab word "al-'ud") players are among the most common

themes of early Abbasid art, as in this Iraqi lusterware bowl of the

tenth century.

Another major contribution was made by the philosopher al-Kindi

(died about 873), who in his treatises discussed the phenomenon of

sound, intervals, and compositions. Al-Kindi presented an

elaboration on the diatonic 'ud-fretting known at his time and

proposed adding a fifth string to the four-stringed 'ud in order to

expand the theoretical pitch range into two octaves. Al-Kindi is

also known for the cosmological links he made between the four

strings of the 'ud and the seasons, the elements, the humors, and

various celestial entities. Comparable emphasis on cosmology and

numerology was presented by the Ikhwan as-Safa', "Brethren of

sincerity," in their tenth century epistle on music.

One of the most prolific contributors was Abu Nasr al-Farabi (died

950), whose Kitab al-Musiqa al-Kabir, The Grand Treatise on Music,

is an encompassing work. It discusses such major topics as the

science of sound, intervals, tetrachords, octave species, musical

instruments, compositions, and the influence of music. Al-Farabi

provided a lute fretting that combined the basic diatonic

arrangement of Pythagorean intervals with additional frets suited

for playing two newly introduced neutral, or microtonal, intervals.

Al-Farabi also described two types of Tunbur, or long-necked fretted

lute, each with a different system of frets: an old Arabian type

whose frets produced quarter-tone intervals,

and another type attributed to Khorasan with intervals based on the

limma and comma subdivisions of the

Pythagorean whole-tone. Discussions on the phenomenon of sound, the

dissonants and the consonants, lute fretting, and references to

melodic modes by specific names are also found in the writings of

the famous philosopher and physician Ibn Sina, or Avicenna, (died

1037.)

Another influential theorist who contributed to the knowledge and

systematization of the melodic modes was

Contact with the

Medieval West

The third major process affecting Arab music was the contact between

the Islamic Near East and

Ivory plaque of the Fatimid period in

The 'ud, known as the "amir al-tarab" or "the prince of enchantment"

was a favorite instrument among composers and amateur performers.

Here, from The Story of Bayad and Riyad, the courtier Bayad sings to

Riyad and her handmaidens.

Influence in the case of instruments is indicated by name

derivations: for example, the lute from al-'ud; the

nakers, or kettledrums, from

naqqarat; the rebec

from Rabab; and the Anafil, or natural trumpet, from al-Nafir. Added

evidence comes from manuscript illustrations of instruments that

have obvious Near Eastern origins. One such document is the

thirteenth-century collection of songs entitled

Cantigas de

The contributions of Moorish Spain to Arab music were profound and

far-reaching. The Easterners' adaptation to a new physical

environment and the introduction of Eastern science and literature

into settings of wealth and splendor, as represented in the courts

of

Moorish Spain also witnessed the development of a literary-musical

form that utilized romantic subject matter and featured strophic

texts with refrains, in contrast to the classical Arabic

qasidah, which followed a continuous

flow of lines or of couplets using a single poetical meter and a

single rhyme ending. The Muwashshah form, which was utilized by

major poets, also emerged as a musical form and survived as such in

North African cities and in the

Tenth Century Abbasid Coin

Falling water activates the drummers on the water clock described

and illustrated in The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical

Devices by al-Jazari.

The fourth major process influencing Arab music was the hegemony of

the Ottoman Turks over

During this period in Arab history, certain aspects of musical life

may have resulted from broader cultural and political contacts. In

the Ottoman world, musicians, like members of other professions,

belonged to specialized professional guilds (tawa'if).

In

The Sama'i (or Turkish saz semai) and

the Bashraf (or pesrev), both

instrumental genres used in Turkish court and religious Sufi music,

were introduced into the Arab world before the late nineteenth

century. Instrumental and possibly vocal and dance forms were

transmitted partly through the Mevlevis,

a mystical order established in

|

All About Arabic Music: Sheet Music, Audio Music, Video Music and Music Education,